Turkey’s ethnic populations are, in a word, surprising.

For example, one would expect that speakers of Azerbaijani residing in Turkey would speak Northern Azerbaijani from Azerbaijan. Yet, according to Ethnologue, the Azerbaijani spoken within Turkey’s borders is Southern Azerbaijani from Iran. This begs the question: are the ethnic Azeris in Turkey from Azerbaijan or Iran? Or both? Of course, all Azeris are ethnically Iranian, and Northern and Southern Azerbaijani are mutually intelligible as far as languages go, but the fact remains that many many Azerbaijanis living in Turkey did not originate where the name suggests.

The same is the case for the Kyrgyz speakers in Turkey who did not immigrate from Kyrgyzstan but were resettled in Turkey’s Kars province from the Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan after migrating into Pakistan through the Hindu Kush in the early 1980s.

Surprised? I'll admit that I was.

|

| Figure 1. Turkey Provinces by Population |

|

| Figure 2. Philippine Languages Map |

When analysts look at a country, they tend to look at the lines that divide it. International borders, provinces, districts, regions, counties, states. They serve as the architecture for how we come to understand a region in a defined geographic space. Turkey, for example, is a country comprised of 81 provinces and 957 districts (See Figure 1) that also plays host to the largest portion of the frequently-imagined Kurdistan in the southeast.

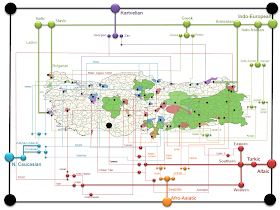

The human geography of Turkey, however, maps a different landscape than that dictated by provincial borders. Borrowing an idea from a Philippine Science blog (See Figure 2), I set out to make my own linguistic map of Turkey (See Figure 3). This map depicts an ethnolinguistically diverse country hosting five language families, over 30 living languages and over 30 minority ethnic populations (for a quick dive into Turkey's linguistic diversity, check out Ethnologue's Turkey page).

|

| Figure 3. Linguistic Map of Turkey |

|

| Figure 4. Ethnolinguistic Areas of Turkey |

|

| Figure 5. Ethnolinguistic Areas of Istanbul |

What began as a geocultural mapping project of Turkey to fill a void in geospatial intelligence quickly evolved into population movement simulations referencing arguably the most prominent humanitarian crisis of today: The Syrian civil war.

Why?

Because no competent analyst can submit a report on minority ethnic populations of Turkey without at least mentioning the approximately 1 million Syrian refugees flooding into the country over the last 12 months (Hatay province was always a microcosm of Syria in Turkey; now that can be said for practically the entire southeastern border ... but more on that later).

The point is that the population movement simulations were only possible with a comprehensive understanding of Turkey's ethnographic landscape in the form of a map which, surprisingly, did not exist prior to the undertaking of this project.

Did any ethnolinguistic maps of Turkey exist? Sure. See Figures 6 and 7 for some of the better examples. But what did they use for resources? How comprehensive were they? How dated were they? These were the questions I asked myself before starting my own collection.

|

| Figure 6. Kurdish Language Map Source: Geocurrents, a fantastic geolinguistics blog |

|

| Figure 7. Turkish Language Map Source: Muturzikin, a Basque Linguistic Mapping Resource |

Using over 200 resources, albeit many with low source reliability, and taking all pre-existing ethnic maps of the region into consideration, I vetted, corroborated, re-vetted and combined everything I could find on all 30 ethnolinguistic groups in order to compile the most comprehensive and up-to-date ethnolinguistic map of Turkey currently available.

Making an ethnolinguistic map of Turkey was my way of walking the battlefield in preparation for the bulk of the project, the simulation, which was yet to come.

Next: Borrowing Analytic Techniques: Populations, Predictions And What Physics Tells Us About The Movement Of Alawites.

***

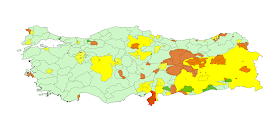

Below are some of the other maps generated throughout the ethnolinguistic mapmaking process. These maps provide ways of looking at the dynamic fluctuation of identified ethnolinguistic areas.

|

| Ethnolinguistic Groups in Turkey According to Origin of Group. Internal (from within Turkey) - Purple External (Such as immigrant or diaspora) - Blue |

|

| Ethnolinguistic Groups in Turkey According to Direction Expanding group - Green Neutral group - Yellow Decreasing group - Orange |