Part 1 -- Let's Kill The Intelligence Cycle

Part 2 -- "We''ll Return To Our Regularly Scheduled Programming In Just A Minute..."

Part 3 -- The Disconnect Between Theory And Practice

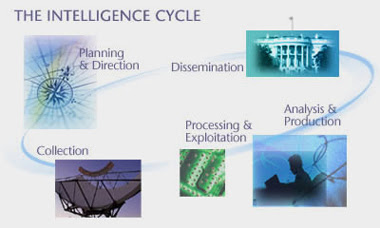

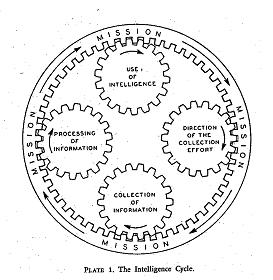

Part 4 -- The "Traditional" Intelligence Cycle And Its History

Part 5 -- Critiques Of The Cycle: Which Intelligence Cycle?

Were the lack of precision the only criticism of the intelligence cycle, it might be able to weather the storm. As suggested previously, there do appear to be general themes that are relevant, and the cycle’s continued existence suggests that its inconsistencies are outweighed, to some extent, by its simplicity.

Unfortunately, the second type of criticism typically leveled against the cycle is much more damning. In fact, it is fatal. Simply put, there is virtually no knowledgeable practitioner or theorist who claims that the cycle reflects, in any substantial way or in any sub-discipline, the reality of how intelligence is actually done.

Consider these quotes from some of the most authoritative voices in each of the three intelligence communities:

"When it came time to start writing about intelligence, a practice I began in my later years at the CIA, I realized that there were serious problems with the intelligence cycle. It is really not a very good description of the ways in which the intelligence process works." Arthur Hulnick, "What's Wrong With The Intelligence Cycle", Strategic Intelligence, Vol. 1 (Loch Johnson, ed), 2007.Once you start looking for them, it is easy to find detailed critiques of the intelligence cycle (and, please, don't hesitate to add your own). The only argument that still seems worth debating is whether or not the cost of maintaining this flawed model of the process is worth the benefit (a question about which readers of this blog were almost evenly split).

"Although meant to be little more than a quick schematic presentation, the CIA diagram [of the intelligence cycle] misrepresents some aspects and misses many others." -- Mark Lowenthal, Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy (2nd Ed.,2003)

"We must begin by redefining the traditional linear intelligence cycle, which is more a manifestation of the bureaucratic structure of the intelligence community than a description of the intelligence exploitation process." -- Eliot Jardines, former head of the Open Source Center, in prepared testimony in front of Congress, 2005.

"The traditional intelligence cycle has been described as an "ideal-type" process that will always be subject to the real constraints of time." -- Jerry Ratcliffe, Strategic Thinking In Criminal Intelligence, 2004

"The classic intelligence cycle is neat, easily displayed, and quickly understood. The problem is that it doesn't really work that way. It's too static, too rigid, with too much distance between leaders and intelligence professionals." -- T.J. Waters, Hyperformance: Using Competitive Intelligence For Better Strategy and Execution, 2010

"Over the years, the intelligence cycle has become somewhat of a theological concept: No one questions its validity. Yet, when pressed, many intelligence officers admit that the intelligence process, 'really doesn't work that way.'" -- Robert Clark, Intelligence Analysis: A Target-centric Approach, 2010.

In addition to the quotes above, my colleague, Steve Marrin, provided me with an interesting update shortly after I started this series. According to him, the intelligence cycle was the subject of "vigorous discussion" at a 2005 RAND/ODNI Conference on intelligence theory and that this topic will also be the subject of a panel at the 2012 International Studies Association Conference. For a carefully crafted and articulate dissection of the intelligence cycle, I don't think I could recommend a better article than Steve's own chapter, "Intelligence Analysis and Decision-making: Methodological Challenges from the 2009 book, Intelligence Theory: Key Questions and Debate).Once again, themes emerge from the general discontent with the inadequacies of the intelligence cycle. Many of these themes I will touch upon as I discuss alternatives to the intelligence cycle in later posts. One theme, however, leaps off each page and tends to dominate the discussion: The intelligence cycle is linear and intelligence, as practiced, is not. Tasks move from one part of the cycle to another like an assembly line, where parts are bolted on in a specific order to create a consistent product.

While this approach might be appropriate for early 20th century manufacturers, it doesn’t work with intelligence, where each product, ideally, contains information that is somehow unique. Consider, for example, this hypothetical dialogue between Mary, the CEO of Acme Widgets and Joe, her chief of competitive intelligence:

Mary: I need to know everything there is to know about the Zed Widgets Company.While this example is simplistic, it makes the point. Intelligence, even in this one minor example within only one of the many parts of the traditional intelligence cycle is, or should be, at least, interactive, simultaneous, iterative. In the above example, this interaction between the intelligence professional and the CEO resulted in a more detailed and nuanced intelligence requirement going, as it did, from the very general, “Tell me everything…” requirement to the highly focused, “Tell me about Zed Company’s Material X costs and give me an estimate of where the price of Material X is likely to go.”

Joe: Sure. What’s up?

Mary: We are thinking about introducing a new widget and I want to know what the competition is up to.

Joe: Anything in particular you are interested in?

Mary: Well, I can see their marketing efforts on the TV every day, so I am not really interested in that. I guess the most important thing is their cost structure. I want to know how much it costs them to make their widgets and where those costs are.

Joe: Right. Labor, overhead, materials. Got it. Is one part of the cost structure more important than another to you?

Mary. They pay about the same amount in labor and overhead that we do so I guess I am most interested in the materials; particularly Material X. That is our most expensive material.

Joe: I just read a report that indicated that the cost of material X is set to rise worldwide. Would you also like us to take a harder look at that and give you our estimate?

Mary: Absolutely.

It is equally easy to imagine this kind of interaction within and between parts of the cycle as well. Collectors and analysts will inevitably go back and forth as the analysts attempt to add depth to their reporting and as the collector develops new collection capabilities. It is even likely that parts of the cycle that are not adjacent to one another will work very closely together, such as an analyst and the briefer responsible for the final dissemination of the product (in its oral form). Decisionmakers, too, may well remain involved throughout the process, seeking status reports and perhaps even modifying the requirement as new information or preliminary analysis becomes available.

The US military's Joint Staff Publication 2.0, Joint Intelligence, states the case more strongly:

"In many situations, the various intelligence operations occur nearly simultaneous with one another or may be bypassed altogether. For example, a request for imagery will require planning and direction activity but may not involve new collection, processing, or exploitation. In this example, the imagery request could go directly to a production facility where previously collected and exploited imagery is reviewed to determine if it will satisfy the request. Likewise, during processing and exploitation, relevant information may be disseminated directly to the user without first undergoing detailed all-source analysis and intelligence production. Significant unanalyzed combat information must be simultaneously available to both the commander (for time-critical decision-making) and to the intelligence analyst (for production of current intelligence assessments). Additionally, the activities within each type of intelligence operation are conducted continuously and in conjunction with activities in each of the other categories of intelligence operations. For example, intelligence planning is updated based on previous information requirements being satisfied during collection and upon new requirements being identified during analysis and production."The situation is even more complex when you imagine an intelligence unit without teams of people working each of the discrete parts of the cycle. In situations involving small intelligence shops, where a single indivdual collects, processes, translates, analyzes, formats and produces the intelligence, the cycle breaks down completely.

The human mind simply does not work in this strictly linear fashion. Instead, it jumps from task to task. Imagine your own habits when researching a topic. You think a bit, search a bit, get some information, integrate that into the whole and then search some more. This approach inevitably leads to analytic dead ends, requiring more collection. At the same time, you are thinking about the form of the final report. If you are putting together an intelligence product that will use multimedia in its final form, for example, you are constantly on the lookout for relevant graphics or film footage you can use, regardless of its analytic value. To even suggest that you should collect all of your information, stop, and then go and do analysis without ever doing any further collection, is absurd.

One of the most recent and widely publicized innovations within the US national security community is the advent of “Intellipedia”, a Wikipedia-like tool for the intelligence community. Wikipedia, of course, is the online encyclopedia that is free to use and editable by anyone. It is one of the most popular sites on the web and, according to at least some research, is as accurate as other generally accepted encyclopedias. It has become, in its short lifespan, the tertiary source of first resort for both analysts and academics.

One of the things it is not is linear. There is no "Table of Contents" and researchers, authors and editors choose their own path through the resource. Some people generate full articles; others only dive in occasionally to fix a particular fact or even a grammatical or spelling error. There are even full-fledged “edit wars” where a particular version of an especially hot topic changes back and forth between competing points of view until either one side gets tired and gives up or, more likely, the sides reach a version acceptable to all. In the end, it is openness and interactivity that give Wikipedia its strength.

The US national security community acknowledged the value of such a tool, at least with respect to its descriptive products, when it launched Intellipedia. Begun in April, 2006, Intellipedia, according to information from June, 2010, now has 250,000 registered users and is accessed over 2 million times per week. This effort, which is clearly far beyond the experimental stage, plainly shows that collaboration and interactivity – the anti-intelligence cycle -- are core to any modern description of the intelligence process.

Next: Cycles, Cycles And More Damn Cycles!