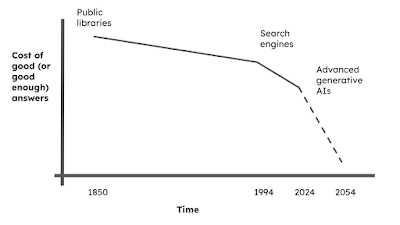

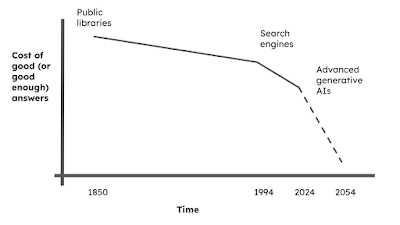

No one seems to know exactly where the boom in Generative AIs (like ChatGPT and Claude) will lead us, but one thing is for certain: These tools are rapidly driving down the cost of getting a good (or, at least, good enough) answer very quickly. Moreover, they are likely to continue to do so for quite some time.

|

The data is notional

but the trend is unquestionable, I think. |

To be honest, this has been a trend since at least the mid-1800's with the widespread establishment of public libraries in the US and UK. Since then, improvements in cataloging, the professionalization of the workforce, and technology, among other things, worked to drive down the cost of getting a good answer (See chart to the right).The quest for a less expensive but still good answer accelerated, of course, with the introduction of the World Wide Web in the mid-1990's, driving down the cost of answering even tough questions. While misinformation, disinformation, and the unspeakable horror that social media has become will continue to lead many people astray, savvy users are better able to find consistently good answers to harder and more obscure questions than ever before.

If the internet accelerated this historical trend of driving down the cost of getting a good answer, the roll-out of generative AI to the public in late 2022 tied a rocket to its backside and pushed it off a cliff. Hallucinations and bias to the side, the simple truth is that generative AI is, more often than not, able to give pretty good answers to an awful lot of questions and it is free or cheap to use.

How good is it? Check out the chart below (Courtesy Visual Capitalist). GPT-4, OpenAI's best, publicly available, large language model, blows away most standardized tests.

It is important to note that this chart was made in April, 2023 and represent results from GPT-4. OpenAI is working on GPT 5 and five months in this field is like a dozen years in any other (Truly. I have been watching tech evolve for 50 years. Nothing in my lifetime has ever improved as quickly as generative AIs have). Eventually, the forces driving these improvements will reach a point of diminishing returns and growth will slow down and maybe even flatline, but that is not the trajectory today.

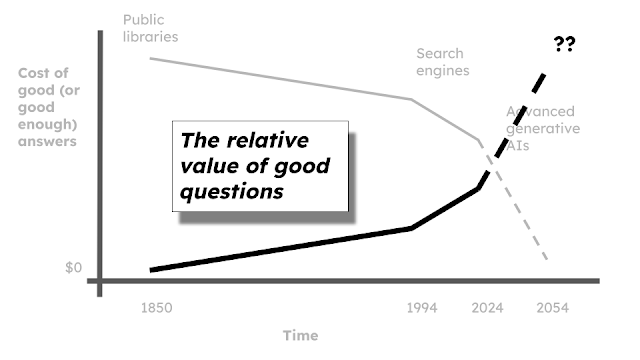

All this sort of begs a question, though: If answers are getting better, cheaper, and more widely available at an accelerating rate, what's left? In other words, if no one needs to pay for my answers anymore, what can I offer? How can I make a living? Where is the value-added? This is precisely the sort of thinking that led Goldman-Sachs to predict the loss of 300 million jobs worldwide due to AI.

My take on it is a little different. I think that as the cost of a good answer goes down, the value of a good question goes up.

In short, the winners in the coming AI wars are going to be the ones who can ask the best questions at the most opportune times.

There is evidence, in fact, that this is already becoming the case. Go to Google and look for jobs for "prompt engineers." This term barely existed a year ago. Today, it is one of the hottest growing fields in AI. Prompts are just a fancy name for the questions that we ask of generative AI, and a prompt engineer is someone who knows the right questions to ask to get the best possible answers. There is even a marketplace for these "good questions" called Promptbase where you can, for aa small fee, buy a customizable prompt from someone who has already done the hard work of optimizing the question for you.

Today, earning the qualifications to become a prompt engineer is a combination of on-the-job training and art. There are some approaches, some magical combination of words, phrases, and techniques, that can be used to get the damn machines to do what you want. Beyond that, though, much of what works seems to have been discovered by power users who are just messing around with the various generative AIs available for public use.

None of this is a bad thing, of course. The list of discoveries that have come about from people just messing around or mashing two things together that have not been messed with/mashed together before is both long and honorable. At some point, though, we are going to have to do more than that. At some point, we are going to have to start teaching people how to ask better questions of AI.

The idea that asking the right question is not only smart but essential is a old one:

"The art of proposing a question must be held of higher value than solving it.” – Georg Cantor “If you do not know how to ask the right question, you discover nothing.” – W. Edwards Deming

And we often think that at least one purpose of education, certainly of higher education, is to teach students how to think critically; how, in essence to ask better questions.

But is that really true? Virtually our whole education system is structured around evaluating the quality of student answers. We may think that we educate children and adults to ask probing, insightful questions but we grade, promote, and celebrate students for the number of answers they get right.

What would a test based not on the quality of the answers given but on the quality of the questions asked even look like? What criteria would you use to evaluate a question? How would you create a question rubric?

Let me give you an example. Imagine you have told a group of students that they are going to pretend that they are about to go into a job interview. They know, as with most interviews, that once the interview is over, they will get asked, "Do you have any questions for us?" You task the students to come up with interesting questions to ask the interviewer.

Here is what you get from the students:

- What are the biggest challenges that I might face in this position?

- What are the next steps in the hiring process?

- What’s different about working here than anywhere else you’ve ever worked?

What do you think? Which question is the most interesting? Which question gets the highest grade? If you are like the vast majority of the people I have asked, you say #3. But why? Sure, you can come up with reasons after the fact (

humans are good at that), but where is the research that indicates why an interesting question is...well, interesting? It doesn't exist (to my knowledge anyway). We are left, like

Justice Stewart and the definition of pornography, with "I know it when I see it."

What about "hard" questions? Or "insightful" questions? Knowing the criteria for each of these and teaching those criteria such that students can reliably ask better questions under a variety of circumstances seems like the key to getting the most out of AI.

There is very little research, however, on what these criteria are. There are

some hypotheses to be sure, but statistically significant, peer-reviewed research is thin on the ground.

This represents an opportunity, of course, for intellectual overmatch. If there is very little real research in this space, then any meaningful contribution is likely to move the discipline forward significantly. If what you ask in the AI-enabled future really is going to be more important than what you know, then such an investment seems not just prudent, but an absolute no-brainer.

No comments:

Post a Comment